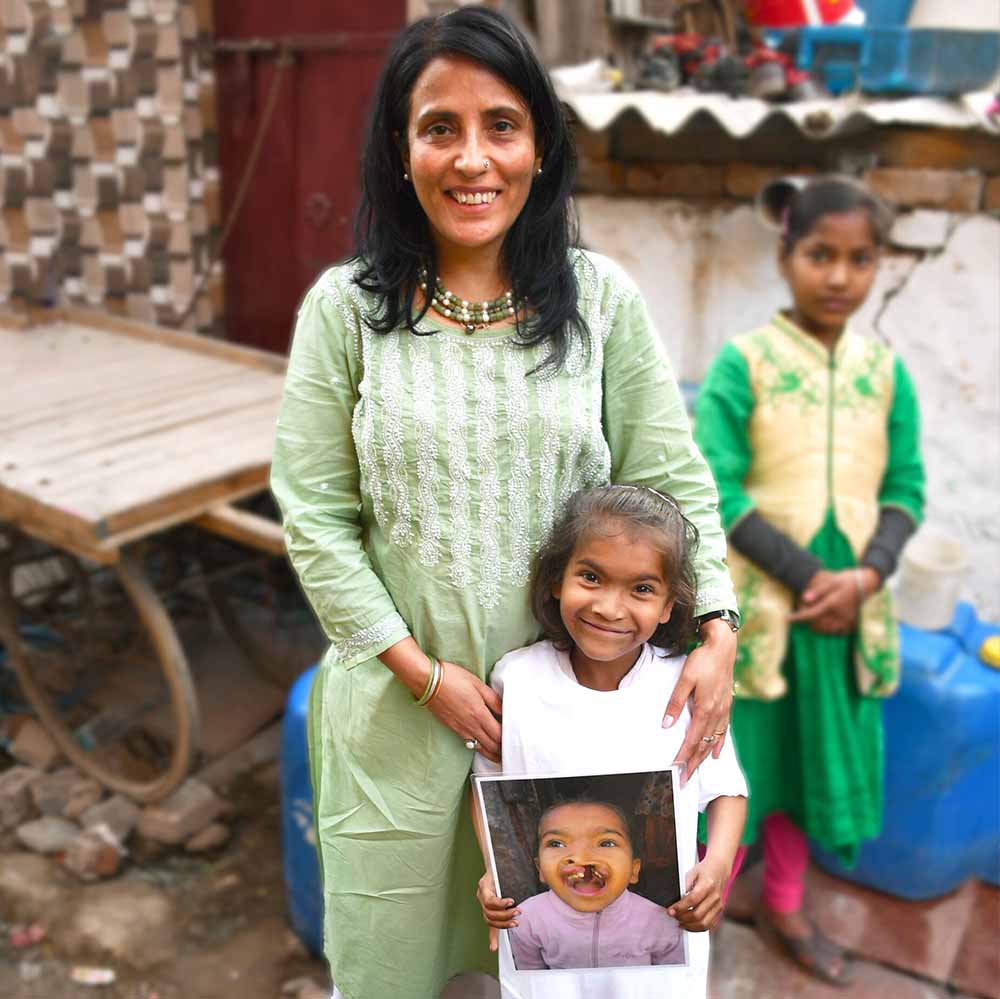

Mamta Carroll: Every Patient is a World in Themselves

Mamta oversees Smile Train's programs from Egypt to the Philippines but sees the whole world in the smile of each individual child.

Based in India, Mamta Carroll is Smile Train’s Senior Vice President and Regional Director, Asia. We caught up with her in February 2020 to discuss her role at Smile Train, her favorite memories in more than 13-and-a-half years with the organization, Smile Pinki, the future of cleft care in Southern Asia, and much more.

How did you come to Smile Train?

I used to work in corporate communications, but I always longed to join an organization that is really doing some good. So when I saw an ad for Smile Train in one of the newspapers, I said, “Oh, wow, that’s interesting,” and I did a little research and I got to know what a cleft is — because at that point, I had no clue. I had never seen a child who had one, I didn’t know anything about it at all.

Then I learned that there were about 35,000 children born in India with a cleft every year, and it really shook me up. So I went through the process of applying for a position, and I was selected, and that’s when my journey started. That was in October 2006. It’s been a great journey and I’ve never looked back.

How do you describe what you do?

I began as a Program Manager, but right now I’m Senior Vice President and Regional Director for Asia. I do a lot of things in this role — my main responsibility is programs, but I also oversee communications and fundraising plus governance and compliance for all 19 countries in the region where Smile Train has a presence — and I hope it will be more than 19 soon, because I am always looking to expand and grow our presence to new countries as well. My team of 18 and I oversee approximately 75,000 surgeries every year over an area that spans from the Philippines to Egypt and includes southern and southeast Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa. In terms of our global presence, my region contributes to 70-80% of the surgeries Smile Train performs.

These are some of the poorest countries Smile Train works in, but also some of the most impactful, because here you can actually be in touch with the beneficiaries and their families directly, and that’s absolutely everything. When you meet a child and their family, you understand that every one of them is a world in themselves. You forget that this is your title, that you’re handling this many countries, and blah blah blah — your whole work is just to help that one child standing before you, and that’s what it is every day. That, to me — that one little child whose life changes and whose family’s life changes — is my goal. That is the work that I do. To me, if I can impact that one life, I’ve done my job.

Are there any patients you’ve met that particularly stand out?

Absolutely! I meet so many of them, every single day. I know Pinki [star of Smile Train’s Oscar®-winning short documentary Smile Pinki] is one of our most famous patients, but I’ve seen that little child right from the day she first came in for cleft surgery, when she was six years old, and now she’s 17. That child is amazing and I’ve seen her whole story, how that little girl who didn’t go out to play, who couldn’t speak properly, couldn’t eat properly, who was teased all the time, has grown into such a beautiful young lady. And she’s so confident — she taught her father how to use his mobile phone, including using WhatsApp and taking pictures, and she plays badminton — she wants to be a badminton champion. I have seen her whole transformation from who she was to who she is today, and there are so many patients like that.

Here’s another one. In the same partner hospital as Pinki had her surgery, GS Memorial Varanasi, once I saw a little baby with a cleft palate who was all shriveled up and crying, and the mother was sick with worry as she tried to feed, because she thought her child was in pain. Well, it was just the lack of milk. Our intervention starts there because that’s when we teach the mothers how to feed their children so they can take in the nutrition they need, because we can’t perform the cleft surgery until the child is properly nourished and reaches a healthy weight. This was such an impactful moment for me — after the training, the mother came up to me with tears in her eyes and said that it was not only the cleft treatment, it’s everything Smile Train is doing: “You taught me how to handle my child, how to feed my own child!” I can’t tell you what that moment was — counseling parents and bringing them up to speed, that’s always very impactful for me.

What do you say when you first meet a patient’s family?

I reassure them. I tell them that we will be there to help inform you of the best treatment options for your child’s cleft. Then we call in a nutritional counselor who will give them the knowledge so that the child can reach a healthy weight for surgery. Counseling is so important – many times the child is too young to know what people are saying about their cleft, but the parents do and the immediate family does. Because in the rural and poorer countries, when a baby is born with a cleft there is often extreme ostracization. Families are in a hurry to have treatment ASAP. So, we do a lot of counseling and reassure the family that surgery will happen, but first the child needs to reach the appropriate weight.

What are the biggest challenges facing cleft care in India and how is Smile Train addressing them?

I think the greatest challenge facing cleft care in India, absolutely hands-down, is lack of awareness. Today, even after 20 years of working in India and doing more than 600,000 surgeries in India, I still think it’s lack of awareness. We have 150 partner hospitals across the country and we help them all raise awareness and do outreach locally; we are also in every state in the country and in 110 cities. But when you talk to educated people in the big metro areas — Delhi, Bombay, Calcutta and all that — and ask them about clefts, their awareness is absolutely negligible. They’ve never seen a cleft, they’ve never heard of a cleft, they don’t know it’s a birth difference, they don’t know that it can be treated, nothing at all. In those places we have to start from scratch.

Have you noticed any kind of change in attitude toward people with clefts in your region since you’ve been working with Smile Train?

I think it’s a work in progress. I wouldn’t say it’s all completely over and people no longer attribute clefts to all these superstitions. Stigma does still exist, that’s reality. We may temporarily feel happy that we’ve addressed it, but I think there’s still a long way to go. In many of the tribal areas where the population usually doesn’t come to the urban centers, there are still a lot of superstitions — and this is also where it’s the hardest to get through to people, to change their mindsets and attitudes. Doing the surgery is often the easiest part, right? Because when the patient comes in, you do the surgery, and then they’re gone. What’s far more difficult is addressing and counseling and changing people’s beliefs and mindsets so that they know that a cleft is a medical condition and that the doctor will help you. That takes a long time. That takes a lot of education, and a lot of one-on-one meetings with the health workers and the social workers. You have to show them examples, make them talk to people who perhaps are a little more educated, who also have a child with a cleft and have benefitted from Smile Train’s services.

Parents’ associations have been incredibly helpful with this. When a mother of a child with a cleft from the biggest town in the state meets a mother who is very poor and has been living under a superstitious belief about where her child’s cleft comes from and tells her, “No, that is not the cause of it. This is a medical issue that could have happened to anyone,” that makes the biggest impact. We are working closely with CIPA, Cleft India Parents’ Association, and the local government health departments on programs like this. They are training their field workers, women especially, to go out, spread the message, and tell the other women that this is not happening for any superstitious reason.

Where do you see cleft care and awareness in India in 10 years? How do you see Smile Train’s role in that?

I think we’ve come a long way in 10 years, and in the 20 years we’ve been in India. As I’ve said, I think it’s always a work in progress because 35,000 more children with clefts are being born every year. So, over the next 10 years, we will have to perform surgery and offer comprehensive care at an even greater rate than we are now to keep up with it.

For awareness, I feel we will have to focus more on raising awareness of the initiatives Smile Train itself is doing, independent of our partner hospitals. The hospitals are doing great work, but it is on us to spread consistent awareness-, reputation-, and brand-building initiatives ourselves at a central, national level. Local hospitals do work to spread cleft awareness, but use their own, local messages. Yes, they do include us, and they do include our branding in all of it, but if we want to really build up our brand awareness, we have to be consistent, and that’s what my team is working on. So, in the next 10 years, probably, I will see more of these national initiatives coming up, and I will see crowdfunding and crowd awareness initiatives driven by the Smile Train India office itself.

I absolutely also see expanded cleft care offerings beyond surgery. I think it’s a pity that out of 150 partners that we have in India, only about 15-16 of them currently offer non-surgical forms of cleft care like speech counseling or nutritional support. I want to double that number or more in the next three years, and then double that again over the next several years so that in 10 years, all of my partners will offer comprehensive care. That’s the goal.

What’s your favorite part of the job?

My most favorite part of my job is talking to parents and having a connection with one patient or another. There couldn’t be a greater blessing than talking to them and counseling them and then actually seeing their lives change after an hour-long surgery. That’s my favorite, favorite thing — going to a beneficiary’s home, sitting with them, talking to them, connecting with them, helping them, and seeing the transformation — not only seeing it, but feeling the transformation, feeling what they feel before surgery. Then feeling what they feel after surgery and enjoying the moment with them. I think that’s the goal. You can see that stats and all that, but at that moment, when you actually meet the patient and their family, nothing else matters.